Hawaiʻi researchers nurture resilient coral to prepare for a future of warmer oceans.

It was a warm, cloudy Saturday at Maunalua Bay Beach Park. Under a blue tent, masked volunteers at the Mālama Maunalua Hana Pūko‘a event bent over water saws to gingerly cut coral into large thumb-sized pieces. Under a green tent, more volunteers stood around waist-high tanks and glued coral fragments—branch side upwards—to aragonite plugs.

These were not ordinary bits of coral. Stress tests at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology’s (HIMB) Coral Resilience Lab, which continues the legacy of renowned scientist Dr. Ruth Gates, showed they were more heat resistant with a better chance at surviving current and future ocean warming than neighboring coral. This is a key trait for coral restoration, since marine heatwaves are expected to continue with increasing frequency and intensity in the coming decades.

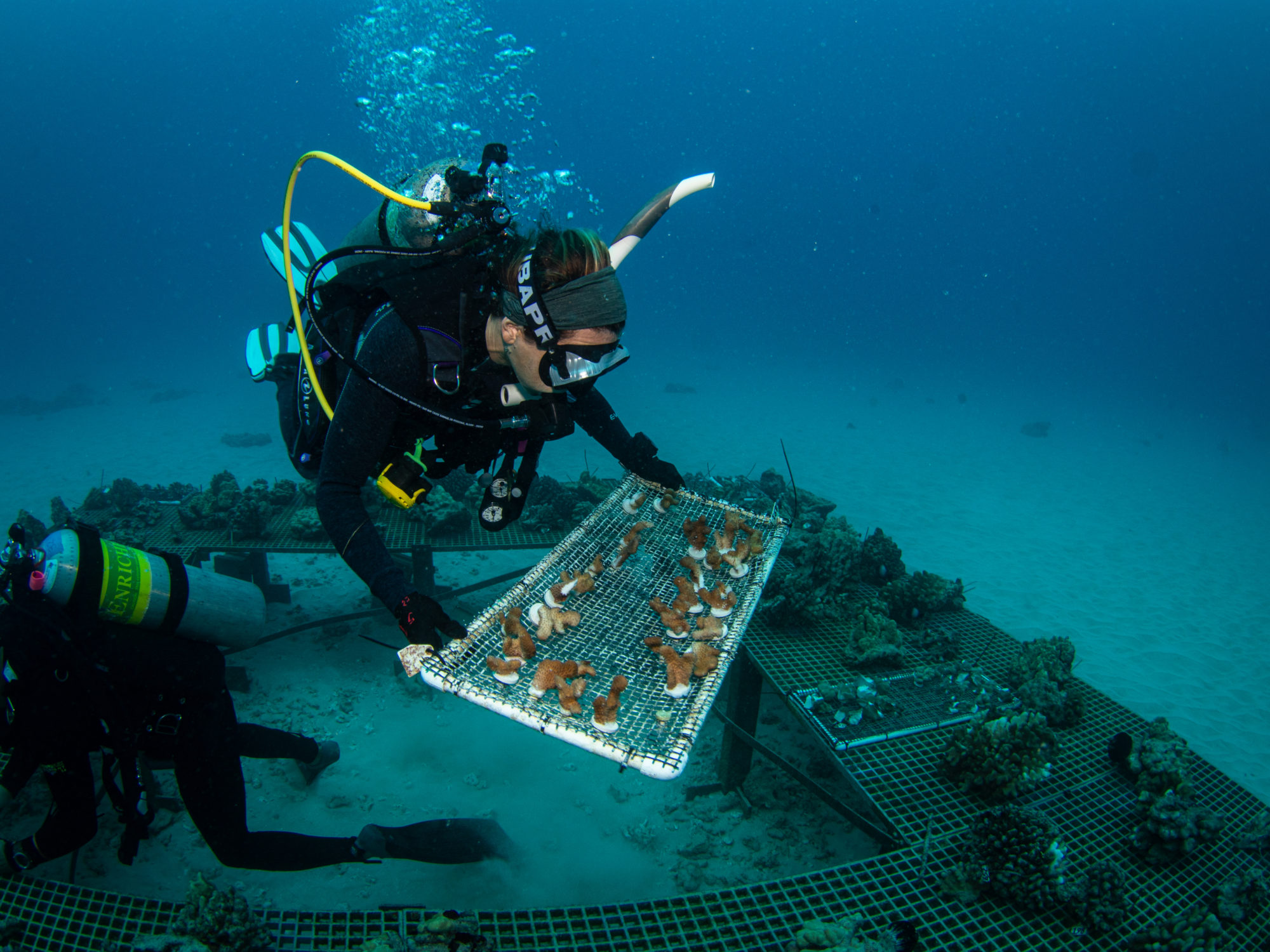

That day, volunteer paddlers, boaters, and divers transported racks of the prepared corals to an offshore nursery. Here, under 40 feet of ocean water, the coral fragments would recover and grow. Then they would be outplanted on reefs with sparse coral where researchers hope the fragments will continue to grow and reproduce to enhance reef resilience.

Borrowed techniques

“We’re just helping the coral adapt faster [to a changing climate] by exposing them to thermal stress, or preferably, breeding parents that we know are thermally tolerant,” says Kira Hughes, program manager at the Coral Resilience Lab.

The lab is using these techniques, borrowed from aquaculture, to restore reefs not just in Maunalua Bay, but in Kāneʻohe Bay and the South Shore of O‘ahu, Ulua Beach and Makena Landing on Maui, and Kealakekua on Hawaiʻi Island.

To ensure neighboring communities are included in the design and implementation of research projects, cultural protocols are often put in place to ensure that Indigenous knowledge and perspectives are respected, valued, and acknowledged, and are included throughout the entire project. For instance, at HIMB, a kūpuna council of lineal descendents of the ahupua‘a of He‘eia advise the director and HIMB faculty on cultural issues, and Hawaiian Civic Clubs are engaged for consultation on individual projects.

Elsewhere in Hawaiʻi and around the world, other scientists, natural resource managers, and community members are also working together to adapt aquaculture and nursery techniques to restore coral reefs. Similar projects in Australia, Curaçao, French Polynesia, Mexico, Philippines, Singapore, and elsewhere in the U.S., to name a few, are outplanting coral grown in land-based or oceanic nurseries, or selectively bred through assisted evolution.

The Hawaiʻi Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) Ānuenue Fisheries Research Center and Coral Restoration Nursery is growing coral in a land-based nursery. At HIMB’s floating nursery, a pilot project increased coral cover from 50 percent in 2017 to 80 percent in 2020.

In 2021, The Nature Conservancy suggested that a restorative kind of aquaculture can help bring back ocean health if the right practices are deployed in the right places. But what is restorative aquaculture?

Urchins, oysters, and limu too

“Restorative aquaculture—that’s applying aquaculture tools to solve environmental problems,” says Dr. Maria Haws, professor of aquaculture at the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo.

A great example is Haws’ proposal to use native oysters, limu, and possibly sea cucumbers to improve water quality in Hilo Bay. Oysters remove excess nutrients from water when they filter-feed on algae. “Limu acts like a sponge and can absorb arsenic and other heavy metals out of the water,” says Rhiannon Chandler-ʻIao, Haws’ collaborator and executive director of the nonprofit Waiwai Ola ʻOhana. “And sea cucumbers can filter water at the sediment level at the bottom of the sea. So what we’re looking at is a multi-species remediation effort, recognizing that different animals and plants have different abilities.”

Elsewhere in Hawaiʻi, other organizations have taken technology from aquaculture and used laboratory-bred oysters to successfully filter pollutants from waterways and wetlands; used lab-grown urchins to effectively clean invasive algae off coral reefs; and outplanted tank-cultivated limu to restore native seaweed populations and to support fish diversity.

Led by research biologist Dr. Mary Hagedorn of the Center for Species Survival, the biobank at the Smithsonian’s National Zoo and Conservation Biology Institute is also exploring cryo-technology to preserve the eggs and embryos of many previously un-bankable aquatic species, such as Hawaiʻi’s native collector urchin.

Charley Westbrook, a graduate student at HIMB’s Toonen-Bowen Lab, has been helping Hagedorn’s team by investigating the best way to cryogenically store egg and sperm of collector urchins for future use in warmer and more acidified conditions.

Westbrook explains that the urchins reproduce at a high rate for a few months out of the year, and then at a markedly low rate the rest of the year. “If one could cryo-preserve their reproductive material at the peak of their breeding season and keep that in storage, you could potentially use that material all year long, to then continuously aquaculture these organisms throughout the year, regardless of any sort of reproductive seasonality,” Westbrook says.

Collector urchins are an important species in Hawaiʻi’s coral restoration because they eat invasive seaweeds that can block sunlight the corals need to thrive. For the last ten years, DAR has successfully used collector urchins to treat more than 227 acres of reef in Kāneʻohe Bay. The agency recently expanded the project to the Waikīkī Marine Life Conservation District to control invasive algae.

Opportunities all over the sea floor

In early 2021, the Coral Resilience Lab and partner Kuleana Coral Reefs collected “corals of opportunity” in Maunalua Bay. “These are corals that are already detached from the reef through wave action, or a ship grounding, or maybe an anchor dislodged it,” Hughes says. “This way we don’t impact the healthy, intact reefs.”

These broken corals are the backbone of the lab’s Restore with Resilience project. Hughes says a lot of Hawaiʻi’s coral reefs have recovered from bleaching events, like the 2014-2015 marine heatwave which caused mass coral bleaching across multiple islands.

“Recent bleaching events have occurred when pockets of warm water come in, and the corals get stressed, and they turn a bright white,” Hughes says. “That often causes the corals to die if that stress is not removed, and they don’t have the opportunity to recover.”

Corals are animals, and just like any other animal or plants, they have a natural ability to adapt. “Earth’s climate is getting hotter. If the increase is gradual, then corals can naturally adapt to that,” Hughes says. “Unfortunately, the current climate trajectory is not gradual. That is why we’re trying to give them a head start.”

So the researchers and community volunteers take these broken-off, basketball-sized corals of opportunity, tag and identify them, and collect test fragments to affix to aragonite plugs. These fragments are transported to the Coral Resilience Lab where researchers expose them to gradually higher temperatures, and temperature variations that mimic natural fluctuations in the ocean.

After weeks of testing, researchers identify the most resistant test fragments. Then they go back to the nursery table to find the original corals of opportunity from which they came. It’s these corals that make it to the Hana Pūko‘a events to be divided into more fragments, nurtured on the offshore nursery table, and later outplanted on the reefs.

This project also preserves the diversity of Hawaiʻi’s reefs because the researchers fragment and outplant only the thermally-tolerant versions of the same species they collected from that location. “We want to keep all of these species that exist here. We want to maintain that diversity,” Hughes says. “But we want to keep those stronger individual corals within each species that have a better likelihood of surviving future bleaching events.”

Coral husbandry

In a companion research project, the lab is testing the ability to breed heat-tolerant coral across generations that could be outplanted on reefs and is developing techniques to selectively breed corals for restoration.

For the past six years, the lab’s researchers, undergraduate interns, and community volunteers have been scooping up or pipetting rice coral (Montipora capitata) egg and sperm bundles from Kāneʻohe Bay during the summer coral spawning season. This happens around the new moon, when the nights are darkest. You can tell when it is the coral spawning season when the ocean smells extra fishy and you can see light-colored oily “slick” along the surface of the water.

The egg-sperm bundles when released “kind of look like Dippin Dots,” Hughes says, referring to the little beads of cryogenically frozen ice cream. “They are actually a couple of coral sperm and eggs wrapped into a tight bundle.”

“What you have there is a renewable source, so you’re not taking from any intact reef in order to create that material,” Hughes says. “And that’s kind of what restoration is all about: having new growth that you put out so you’re enhancing wherever you’re outplanting.”

Engaging communities

Hughes offers a caveat for readers to think about, however. “The biggest challenge, which we’ve known from the very beginning, is that everything we’re doing just puts a band-aid on the problem,” she says. “If we don’t tackle climate change at a broader scale none of this is going to matter, because it’s just going to get too hot for even the more resilient corals to survive.”

Restoration is also hard to expand to a large enough scale that makes a big difference, she says. The Coral Resilience Lab has a handful of research projects in several locations across Hawaiʻi. But how much restoration will be enough?

“That’s why we’re bringing on a bunch of partners, and we’re making sure that we expand to other islands within Hawaiʻi and involving the communities,” Hughes says. “These Hana Pūko‘a events are the first time we’ve attempted to include the community in coral restoration practices, because honestly, I think that’s what is needed in order to be successful.”

Lillie Flynn, a 22 year-old volunteer from Hawaiʻi Kai agrees, and doesn’t plan on missing a Hana Pūko‘a if she can help it. “It was exciting to work—especially in a bay that I surf in and swim in—to help with coral resilience, and it was great to get the whole community involved,” she says. “And just to get the opportunity to ask scientists questions that I have about the corals, learn about the projects that they are working on, I just found it really exciting.”

Originally published in Ka Pili Kai Kau, Hawai’i Sea Grant’s science magazine. See the original publication here.

Banner Image: A volunteer diver prepares to secure a rack of fragmented resilient coral to an underwater nursery table in Maunalua Bay, O’ahu. The coral fragments recover on the table for about two weeks before being outplanted to the reef. Photo: Richard Chen